There are literally hundreds of practices which can be listed under the heading of ‘meditation’. All these have in common the ability to bring about a special kind of free-floating attention where rational thought is bypassed and words are of far less importance than in everyday life. It is characteristic of this state that when in it, the person is completely absorbed by his particular object of meditation. If something else comes to mind, it will usually drift in with a sort of vague, faraway quality, and then drift out again.

There are literally hundreds of practices which can be listed under the heading of ‘meditation’. All these have in common the ability to bring about a special kind of free-floating attention where rational thought is bypassed and words are of far less importance than in everyday life. It is characteristic of this state that when in it, the person is completely absorbed by his particular object of meditation. If something else comes to mind, it will usually drift in with a sort of vague, faraway quality, and then drift out again.

The devices used to bring about this state are as diverse as gazing quietly at a candle flame; attending to the mental repetition of a sound (mantra); following one’s own breathing; concentrating on the imagined sound of rainfall; chanting out loud a ritual word or phrase; attending to body sensations; concentrating on an unanswerable riddle (koan); passively witnessing the flow of thoughts through one’s mind; or whirling in a stereotyped dance.

Whatever, the aim is the same: to alter the way the meditator experiences one’s own existence. All these techniques close out the distractions of the outer world in much the same way as an isolation chamber. In a sensory-deprivation experiment the subject is removed from incoming sense impressions by being placed in a soundproofed room, by wearing goggles to eliminate patterned vision, or by undergoing other sense-reducing manipulations.1 In meditation, the meditator removes his attention from distracting sense impressions and thoughts by creating an inner ‘isolation chamber’ of his own making. It is when the outer world is removed that meditation can take effect and the individual is said to become ‘centered’.

In the meditative traditions the words ‘centered’ and ‘centering’ refer to the restoration of an inner balance accomplished through the use of devices which serve to focus the mind. This process is seen as acting like a psychological gyroscope which stabilizes mind and body and neutralizes the tendency to pull away from the center of one’s being.

Despite the fact that attention is directed toward a meditational ‘object’, however, each technique copes with a basic property of meditation which can best be described as a counter-tendency, a need to pull away from the object of focus. Even the calm and centered mind is not entirely still. Periodically it reaches for renewed contact with the environment, either through sense impressions or thoughts, and each meditational system has its own way of dealing with this ‘outward stroke’ of meditation.

Some systems are not permissive, or may even be coercive with respect to the handling of ‘distractions of the mind’ during meditation. A non-permissive form of meditation will demand strict concentration on the meditational object. Practitioners will be directed to pinpoint their attention, to banish intruding thoughts from their mind by an act of will, and to return immediately and forcefully to the object of focus whenever they find their attention has wandered. This approach is seen in extreme form in instructions given to a meditator in a fifth century Buddhist treatise dealing with thoughts that may intrude into the meditation:

. . . with teeth clenched and tongue pressed against the gums, he should by means of sheer mental effort hold back, crush and burn out the [offending] thought; in doing so, these evil and unwholesome ideas, bound up with greed, hate or delusion, will be forsaken, then thought will become inwardly calm, composed and concentrated.2

In contrast, many meditative systems use varying degrees of permissiveness toward intruding thoughts. In these more permissive techniques, the meditator is instructed to return gently and without effort to the object of focus.

At the time of writing Freedom in Meditation, there had been no experimental findings dealing with the effects on the meditator of permissive versus non-permissive forms of meditation, however, some recent research, using brain imaging has revealed some fascinating findings.

Concentrative versus Non-Directive Meditation

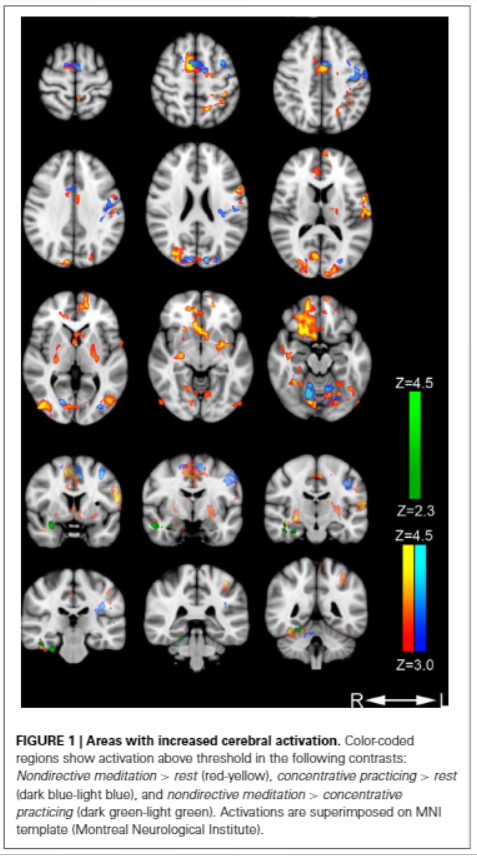

Published in the Frontiers in Human Neuroscience in 2014, a research article on “Non directive meditation activates default mode network and areas associated with memory retrieval and emotional processing”3 revealed notable differences in brain activity, in comparison to a state of rest and between focused attention meditation, commonly found in Buddhist practices that utilize focusing, on a sound (such as transcendental meditation), statement, or feeling, open monitoring (of choice-less awareness) meditation (mindfulness forms of meditation), and non directive meditation, similar to Clinically Standardized Meditation (CSM) and Acem meditation (both of which are cited in the research article.)

The particular focus of the research was involved with default mode network (DMN) of the brain. This network is known to to be associated with different functions, such as:

Thinking about one’s self (introspection), thinking about others, remembering the past, and envisioning the future. In other research, the default mode network has shown to deactivate during external goal-oriented tasks such as visual attention or cognitive working memory tasks.

In this study, the researchers hypothesized and set out to discover if accepting the spontaneous flow of thoughts, images, sensations, memories, and emotions as part of meditation, without any emphasis on reducing, monitoring, evaluating or directly relating to it, would increase mind wandering and activation of the default mode network, compared to practicing with more emphasis on control and a concentrated focus of attention.

What they discovered is that non directive meditation seems to involve more extensive activation of the default mode network, as opposed to the other forms of meditation, including brain areas associated with episodic memories and emotional processing (mind-wandering).

While writing my book, I had suspected that the effects experienced by a meditator may be different if he or she mistakenly interprets their form of meditation as being non-permissive when it is not. Most techniques for meditation require that the meditator make no conscious effort, but ‘let things happen’ rather than make them happen.

Often, however, the average person automatically injects coercion into a meditative practice unless carefully trained to do otherwise. The result is roughly the same as it would be if a stern teacher were standing close by and commanding one to ‘shape up’ the whole time one meditates.

A non-permissive approach to meditation (self-produced or produced by instructions from someone else) can sometimes increase guilt in the meditator as blame may emerge for not meditating ‘correctly’, or for the kinds of intruding thoughts that are being evoked.

A permissive approach, on the other hand, because it encourages an accepting attitude toward the thoughts or feelings, which may inadvertently arise during meditation, may help the meditator to handle previously unacceptable feelings that might have been hidden or ‘repressed’. It may also help release emotional tensions, because these have an opportunity to play themselves out during mind wandering in this more permissive state.

For further insights see:

Mantra versus Mindful Meditation

Dr. Pat vs the TM Organization: Length of Meditation Dispute

Discover Clinically Standardized Meditation (CSM)

A Gentle, Easy-to-Learn, and Permissive Form of Meditation

As the study of meditation continues to evolve, the mysteries of it are continually being revealed…

By Patricia Carrington, Ph.D.

Derived from “Freedom in Meditation”

1. Meditation journal of George Edington (personal communication)

2. E. Conze, Buddhist Meditation (New York: Harper, 1969), p. 83.

3. Xu J, Vik A, Groote IR, Lagopoulos J, Holen A, Ellingsen Ø, Håberg AK and Davanger S (2014) Nondirective meditation activates default mode network and areas associated with memory retrieval and emotional processing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:86. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00086